Linda Grant is one of my favourite writers. She has written five works of fiction, of which I have read three and liked all of them. She was shortlisted for the Man-Booker prise in 2008 for her novel The Clothes on Their Backs, and won the Orange prise for her second novel When I lived in Modern Times.

She has also written non-fiction, which I have not read (yet) although I have in my collection Remind Me Who I Am, Again, Grant’s account of her mother’s descent into Alzheimer’s Disease, and I intend to read it one of these days when the mood is right (what sort of mood you have to be in to read an account of a progressive, incurable disease with hundred percent mortality?).

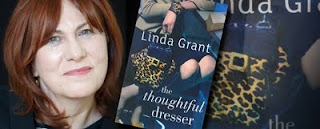

I wasn’t sure that The Thoughtful Dresser, Grant’s collection of essays on fashion, would be my cup of tea. I was probably not the target reader of the book (I felt), which was advertised as ‘the thinking woman’s guide to our relationship with what we wear: why we want to look our best and why it matters.’ The subject matter is not of great interest to me, or so I thought. When it comes to clothes I am one of those people whom Grant claims to have occasionally come across: people who ‘apparently’ do not care for clothes and wish they did not have to be bothered with them, apart from the primitive functions of covering themselves up. (Grant uses the gender neutral noun ‘people’, which includes both men and woman. I have always thought, in submission to the century old cliché, and based on my knowledge of the limited circle of men and women I know, that most men, heterosexual men in any case, are less interested in shopping for clothes than women.) My approach to what I wear, I realised after reading one of the essays in the book, is utilitarian. Clothing, for me, is about following a set of basic social rules, although that is not necessarily in order to, as Grant speculates, free up my mind to think about something else; I just find clothes and shopping for clothes about as interesting as watching a football match between Tottenham and Hull (that is, not interesting at all). I am no boffin but sometimes I suspect that it is really because of the way my brain is wired up; maybe there is a gene for shopping for clothes which I (and most of the men I know) lack.

I therefore borrowed the book from the local library with some apprehension. I was not sure I was going to like it, and borrowed it only because, as I said earlier, Grant is a favourite author.

I am pleased to report that Grant did not disappoint.

The book is not just about clothes and shopping for them—although there is a lot of it—; in these essays Grant tells the story of her immigrant Jewish family—both sets of her grandparents arrived in the UK from Eastern Europe at the turn of the nineteenth century—and its attempt to assimilate with the adoptive culture. And clothing played an important part in the assimilation process. When her grandfather walked out of the ghetto every day, he had to look the part. Both of her grandfathers—who, Grant informs, started very humbly, like Simon Marks who founded Marks & Spencer; but, unlike Marks, they did not strike it rich—followed the dictum that the only thing worse than being skint is looking as if you’re skint. For Grant’s mother, shopping was an all absorbing activity; an activity that was not to be taken lightly; that required stamina and acquired skills. So much so that when she died her daughters—who have inherited their mother’s interest in clothes—put the following notice in the Jewish Chronicle:

“ . . . She taught us to respect others, that chicken soup can cure almost everything and a good handbag makes the outfit.”

(How I wish Grant, while she was in the reminiscing mood, mentioned how she came to develop an interest in books, reading and writing; from whom did she inherit it? Or was it a gene mutation?)

Another inspiring story, told in three different sections, is of the fashion doyenne Catherine Hill. The story of how Hill, born Katerina Deutsch in Kosice (Kassa in old Hungarian), Hungary, how she survived Auschwitz, then destitution, and finally a loveless marriage to reinvent herself as a successful fashion entrepreneur is the triumph of human spirit over adversity.

Grant also traces the changes in the European women’s fashion from the Victorian era and attempts to link them (perhaps predictably) to the emancipation of women’s status in the society. She says that the purpose of the discourse is not to put forth a theory of fashion; but it is a fairly persuasive theory. In this context Grant also writes about the ‘niqab’, the all-encompassing chador, worn by some Muslim women. The usually outspoken Grant is very careful, as though anxious not to court controversy, when she writes about the Islamic dress, although she drops less than subtle hints as to what her views are when she describes it at one time as ‘not I understand to be clothes at all’, and at another as ‘medieval black sheet’. Her conclusions, nevertheless, are very considerate (‘the teen age daughter of assimilated Muslim parents who chooses to wear the hijab as a statement of religion and culture is no more anti-fashion than the African-American men and women who in the 1960s made a similar point by abandoning the scalp-burning, hair-straightening chemicals and letting their hair grow into Afros’; and ‘Were I a young Muslim woman in post-9/11 and post-7/7 Britain, I too would be considering how to use my clothes to make a point’) and disappointingly anodyne.

These, however, are minor quibbles. The Thoughtful Dresser is an entertaining read. But it is more than that. It makes you smile; it makes you sad; and, above all, it makes you think of the world we live in from an angle you have not done before. What more can you ask of a writer?